Introduction

Real-world data (RWD) plays a crucial role in medical research, providing valuable insights from a variety of sources including electronic health records and claims databases. However, unlike randomized controlled trials, allocation is not random. This can result in confounding.

Understanding and addressing confounding is essential for valid causal inference. This blog post explores challenges due to confounding when using RWD, the role of causal estimands, and statistical methods to mitigate bias. Time-varying confounding involves slightly different methods which will not be covered in this post.

The Impact of Confounding

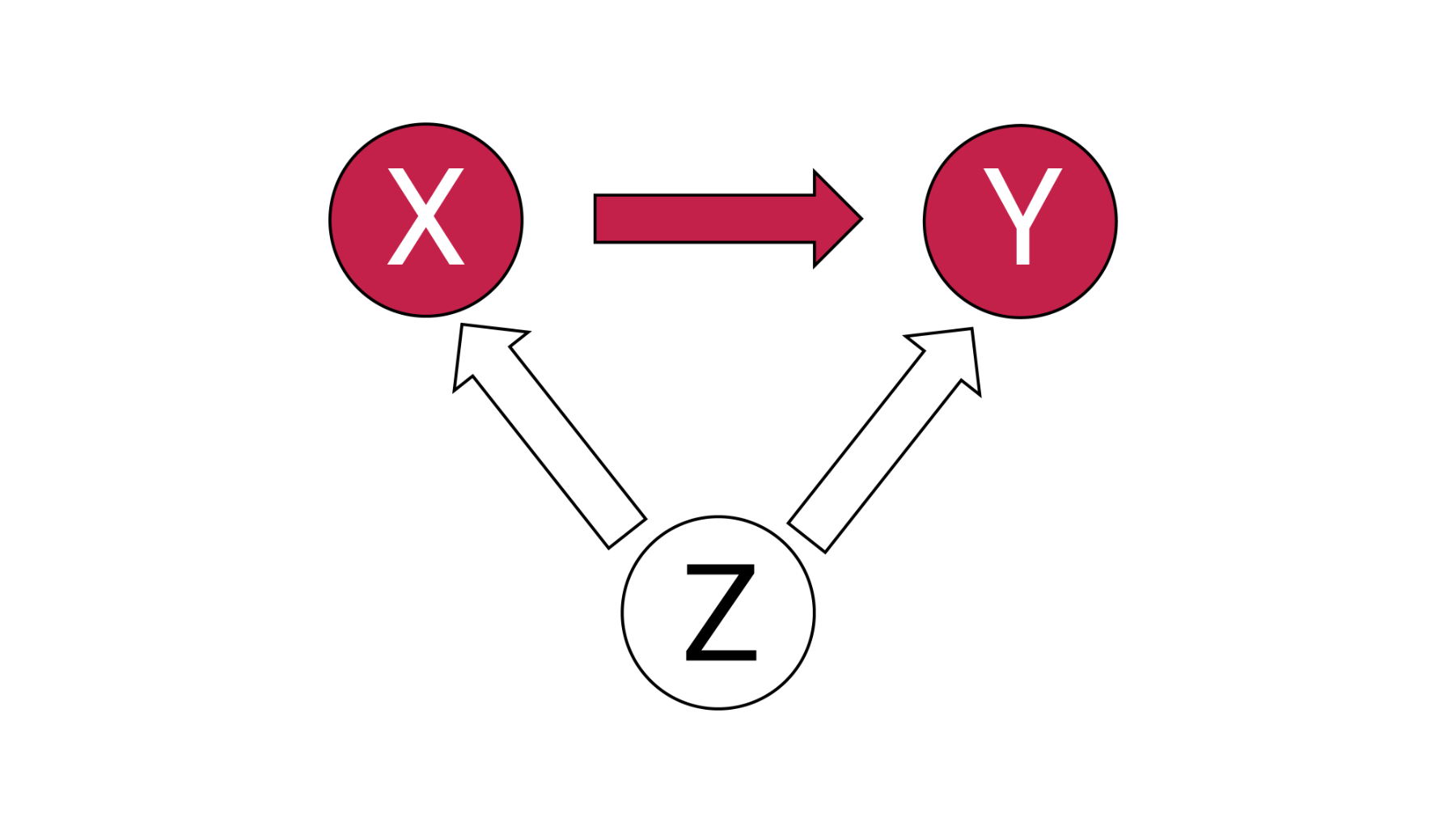

Confounding occurs when a variable causes both the treatment and outcome (Figure 1).

Figure 1 – Confounding due to Z

Failure to account for confounding can obscure the true effects of an intervention, resulting in incorrect conclusions that can impact decision making. Confounding is a major threat to the validity of a study, particularly in non-randomized studies.

Causal Estimands: Aligning Analytical Approach with Study Objectives

A causal estimand defines the effect of interest, specifically the who and what. Is the average effect of people who were treated of interest? Those who were untreated? Or something else?

There are four common causal estimands:

- Average treatment effect (ATE)

- Average treatment effect in the treated (ATT)

- Average treatment effect in the untreated (ATU)

- Average treatment effect in the overlap (ATO)

Deciding the causal estimand of interest is a key part of any analysis. Different adjustment techniques align with different estimands, influencing how results should be interpreted. [1,2]

Methods for Addressing Confounding

There are two categories of confounding: unmeasured and measured confounding. Unmeasured confounding is best assessed using sensitivity analyses. For measured confounding, there are several techniques. These can be categorized into three groups: modelling the outcome, modelling the treatment and modelling both. A few popular approaches:

- Outcome Regression: This models the outcome as a function of treatment and covariates. By incorporating confounders into the model, outcome regression estimates the relationship between the treatment and outcome while controlling for confounding. [3]

- Parametric G-Formula: The parametric g-formula fits a parametric model using the available data. This model is used to predict the outcome for both scenarios: if the individual received treatment and if they did not receive treatment. The difference in these values is the treatment effect. This can be used to calculate the average treatment effect. This method is part of a broad class of methods, referred to as g-methods.

- Propensity Score (PS)-Based Methods: A propensity score is the probability of assignment to a particular treatment group based on observed covariates. [4] Several techniques use the propensity score including matching, weighting, stratification and inclusion as a covariate. This helps to balance observed confounders between groups. [5]

- Doubly Robust Methods: Doubly robust methods combine two models: a treatment model and outcome model. These methods provide valid effect estimates if at least one of the two models is correctly specified.

- Sensitivity Analyses: Sensitivity analyses can be quite helpful. For unmeasured confounding, there are several approaches that can be leveraged to assess the potential impact. [6] These methods can help to quantify the magnitude of unmeasured confounding to substantially impact results. Sensitivity analyses can also be used for measured confounding. An example is the Bayesian parametric g-formula. This method can be used to assess the impact of different strengths of confounding on the result. [7] This can be leveraged to check the robustness of results.

Conclusion

Confounding presents a significant challenge when analyzing RWD. Several methods are available for addressing confounding, however choosing the right tool is crucial. The causal estimand should be considered when selecting a technique to ensure the correct question is being answered.

At Phastar, we specialize in applying advanced statistical techniques to ensure the integrity of RWE in clinical research. As RWE plays an increasingly important role in regulatory and clinical decision-making, ensuring rigorous methodological approaches is essential to generating high-quality, reliable insights.

References

1. Greifer, N., & Stuart, E. (2021). Causal Estimands: What They Are and Why They Matter for Confounding Adjustment. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2106.10577

2. Desai, R. (2019). Methodological considerations in causal inference using real-world data. BMJ, 367, l5657. https://www.bmj.com/content/367/bmj.l5657

3. Hamilton, D. F., Ghert, M., & Simpson, A. H. R. W. (2015). Interpreting regression models in clinical outcome studies. Bone & Joint Research, 4(9), 152–153. https://doi.org/10.1302/2046-3758.49.2000571

4. Rosenbaum, P. R., & Rubin, D. B. (1983). The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika, 70(1), 41–55. https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/70.1.41

5. Austin, P.C. (2011). An Introduction to Propensity Score Methods for Reducing the Effects of Confounding in Observational Studies. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 46(3), 399–424. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3144483/

6. Hernán, M.A., & Robins, J.M. (2020). Causal Inference: What If. Chapman & Hall/CRC. Causal Inference: What If (the book) — Miguel Hernán

7. Howards, P. P. (2022). Sensitivity analyses for unmeasured confounders. Epidemiologic Methods, 9, 361–375. https://doi.org/10.1515/em-2022-0031